Interdisciplinary Art

/To accompany the release of my book I created a series of social media posts and videos featuring original content, music, and graphics. The visual aesthetics of the project include abstract images which are representations of cymatics — the visual patterns that emerge in liquid when exposed to auditory vibrations. Each chapter of the book features a unique cymatic pattern. The images are vector graphics and I am able to use them across a variety of media types including video productions. I originally drew these by hand with a spirograph, and then scanned, vectorized, and brought into Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, and After Effects for modification, colourization, and animation.

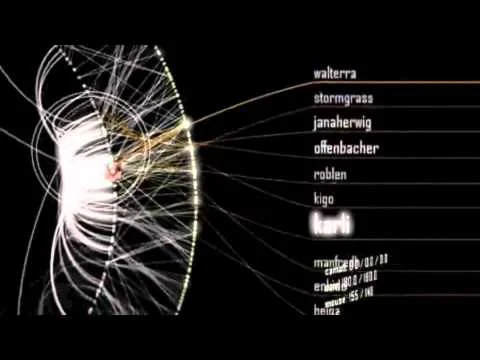

I created four videos each with its own original musical composition. Three of the videos are short abstract cymatic visualizations with voice-overs. The other is an in-depth educational exploration of the impact of software on music. I also created versions of the visualizations without voice-over in order to focus the music production.

One noteworthy aspect of my music production process is the use of guitar as a MIDI controller. Through my guitar I can control any synthesizer. Many people don’t realize that there are a variety of MIDI controllers beyond the keyboard including guitar, saxophone, drums, and many others. My conventional guitar playing is also featured on all the videos, and I play or program all of the other parts including synthesizers, basslines, drums. I mixed and mastered the tracks, and synchronized the music with the visuals.

I continue to produce multimedia projects and these production activities serve as a foundation for teaching music and media topics. My passion for making music and digital art means that I stay up to date with a variety of important trends and new technological developments in music production.

Questions

This song is conceived as a digital chant. It features a distorted bass line, a variety of keyboards, and notably my guitar harmonizing with a choir synthesizer.

Kaleidoscope

This song is arranged for electric guitar and drum machine. Several guitars play together while the drum machine utilizes only the bass drum and a clap sample.

AESTHETIC

This song is devised as computer funk and is inspired by the genre of vaporwave. It features an out of control bass synthesizer and heavily effected drum machine.